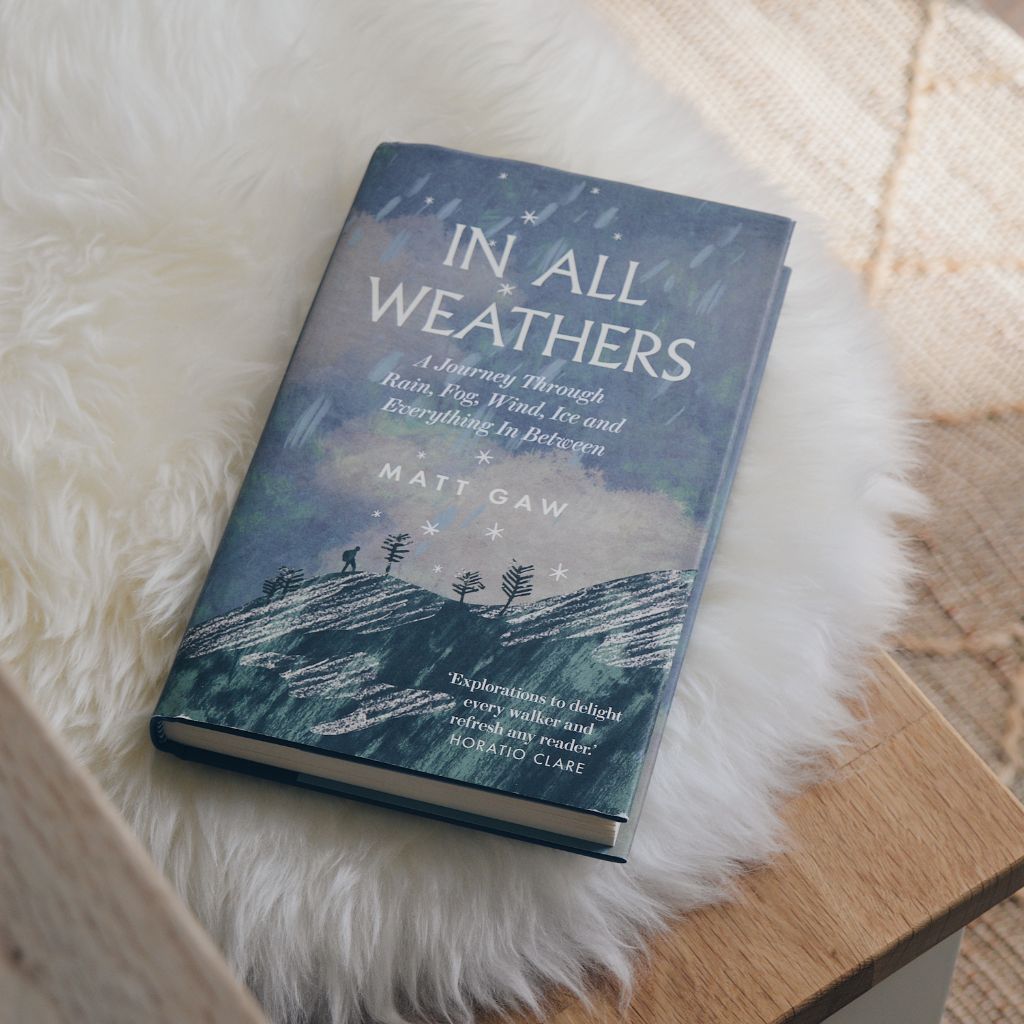

Right now I’m reading In All Weathers, a review copy gifted to me by the publishers. It’s probably the most enjoyable nature writing I’ve come across in a while.

In the book, author Matt Gaw pays almost devout attention to the often-berated British weather: rain, sleet, snow, ice, fog, wind. The sentences are taut, often poetic, and sunshine plays a secondary role.

In the section on wind, Matt visits a weather station at Cambridge Botanic Garden. These stations are all, Matt says, “designed to turn the weather into codes. To translate experience into something that can be counted, compared and stored.”

This got me thinking about what is lost — and what can be gained — when you take an experience and distil it into data. Echoing, curiously, my latest written work for Issue 08 of Hidden Scotland magazine.

The first is a profile feature on Edinburgh-based artist Ploterre. Rebecca creates artwork using data about nature, often inspired by Scotland’s landscapes and coasts. But her designs are more than simply beautiful.

“There’s a visual language in nature, so every mark on the page is linked to data in some way. The shape of a tree ring, the pattern of a leaf, how water flows,” Rebecca explains.

For Ploterre, translating outdoor experiences into art can inspire us to see the environment around us in new ways — and take action to protect it. For example, Rebecca’s involved with Trash Free Trails, a network of volunteers working to count, clear, and educate people about litter in our wild places.

In this way, recording codes and trends in the outdoors raises awareness of how we can come together to safeguard our green spaces for future generations.

There are also numbers in food, which forms the focus of my second article for the magazine. I interview Gareth Cole, the multitalented owner-chef-brewer-author of Café Canna, a restaurant on the Inner Hebridean island of the same name.

Food itself is often expressed as data: the number of ingredients, the volume or weight of each, the temperature at which they’re cooked and for how long, and the amount of people they can serve. All of these add up to the edible experience itself — flavours which, on Canna, are deeply linked to the local environment and the people.

“Just about every single one of the island’s residents is involved in some way in the plate of food you’re eating,” Gareth says. Diners can watch the fishing boats return with the langoustines they’re about to eat; join Gareth the next morning to forage for seaweed on the beach; and even book a table over the radio if they approach the island under sail.

Café Canna re-opens for the season this weekend. I wonder what the weather is like there today. The wind and rain have a steadfast influence on island life and will likely determine the number of visitors the restaurant welcomes this year.

Perhaps we’re all hoping for a gentler summer. Where numbers and forecasts help us imagine a place and what we might find there, before the magic unfolds with the tides as we come ashore for the first time.